Latitude

Latitude, noun:

A geographic coordinate that specifies the north–south position of a point on the Earth’s surface.

Scope for freedom in action or thought.

The extent to a which a light-sensitive material can be over- or under-exposed and still achieve an acceptable result.

Loch Lomond Moonlicht

Disturbed perspectives

In his landmark Ways of Seeing, John Berger notes that “perspective makes the single eye the centre of the visible world”. I have often felt that our contemporary ways of seeing landscapes—perhaps particularly when viewed through the medium of photography—are constrained by perspectives that have become all the more powerful for being completely unacknowledged. As viewers, we are all used to leading lines, the rule of thirds, and the deep focus that ensures sharpness from foreground to vanishing point. We search for the interesting elements that immediately draw us into a natural scene; we happily follow the inviting rivers and curving paths that carry us up a mountain or along a valley. As viewers, we may not know what we are looking at—we may not name that device as “the Golden Ratio”—but such unspoken aesthetic and mathematical conventions govern our understanding of place and space, of nature and culture.

Berneray Seascape No. 1

Photography and photographers thus have a powerful capacity to mediate how landscapes are seen, and to fix (and sometimes ossify) human perspectives. But might a photographer also have the capacity to trouble perspective? Latitude began with this question, and by extension with a questioning of my own practice as a landscape photographer. Could I, with my camera, endeavour to disturb the self-centring effect of landscape photography’s “single eye”? Was there a way that I might represent the beauty of the places that I loved to look at a little differently? A way that might illustrate the constraints of photographic perspective by disturbing perspective itself? Might I, by ignoring compositional conventions, by removing distractions, and by replacing the representational with the abstract, connect the viewer to a landscape in a new, non-perspective-centric way? Could I use photography to distil a sense of place into pure form? How would my images appear if I focused on the felt experience of a landscape rather than what it was expected to look like?

Hebridean Night No. 2

What are you looking at?

This project is an exploration of Latitude in all senses. Literally, it is an exploration of the landscape within a defined latitude (55°–57°). But by giving myself the freedom, or latitude, to make photographs without the compositional (and implicitly ideological) constructs that govern so much contemporary landscape photography, I have been able to present images in which aesthetic convention has effectively been replaced by essential form. My influences may be very obvious: in photographers such as Hiroshi Sugimoto and Franco Fontana and visual artists such as Mark Rothko and Patrick Heron. Most of the images I have chosen for this collection are indeed abstractions, creating an impression of space with washes and blocks of colour. While my use of abstraction aims to intensify a sense of experience over representation, these remain real spaces and real places.

Berneray - East Beach

Could this image – “Berneray—East Beach” – really portray anything other than the place where Hebridean land meets water?

Seascape at Uig

“Seascape at Uig” speaks to me so strongly of the quality of the dying evening light where the sea meets the sky across the Minch. I can’t think where else this might be, other than the Isle of Skye.

The slow shift in light as the sun sets over the Trossachs is familiar, and deeply humbling, to me. I can think of no better way of depicting this quality of light, this feeling of nature’s surpassing of—and ultimate indifference to—the human, than the two images I have chosen to include in this collection

Trossachs No. 5 // Surpass

Trossachs No. 7 // Indifference

So yes, abstract these pictures certainly are, but they have also been made with direct and explicit connections to landscapes at this latitude, to the this-ness of my natural environment and my particular human experience of it.

Control versus chance

Balancing chance and control has been crucial in making many of the images in this portfolio. The horizon—either the actual horizon or an implied one—is the central theme which ties all the images together. To quote the Proclaimers, “The best view of all is where the land meets the sky”. This strong central motif is dependent on a tightly controlled horizontal composition. However, my use of intentional camera movement during the exposure introduces a huge element of chance. Within a genre (landscape photography) that’s known for its careful, staged compositions, this fluidity, this random, chance element can be highly liberating. Rather than the eye being drawn to specifics or led by perspective, the resulting image is impressionistic, fluid, minimal. Chance and control combine in these photographs as I gradually moved away from a perspective-based image to an expressionistic one. What I ended up with were distilled landscapes, images in which place and time were reduced to their most basic elements. The scenes chosen here are presented to the viewer in a non-representational way—stripped down to pure form—but they are also, I hope, highly evocative of particular seasons, moments, spaces.

Carbeth No.1 // Frozen

The element of chance is at the heart of Latitude, but often it was only through repetition that I developed a deeper understanding of a scene and how it I might best reach my vision of how to convey it. As is often the case in my work, by allowing myself the latitude to fail, my creativity in this project was an iterative process—making, remaking, correcting and refining. This repetition might involve me shooting the same location in different seasons or at different times of day or night, from different angles or elevations. I experimented extensively with techniques of allowing the scene to move in relation to the camera, or vice versa. I shot (and printed) on different media from black and white 35mm film to infrared digital sensors. I used analogue cameras, digital cameras, long lenses, wide lenses, pinhole lenses, light-modifying filters and more. I printed with different chemicals in the darkroom, I re-touched digitally in post-production … always with the thought of balancing the elements of chance and control within my creative processes.

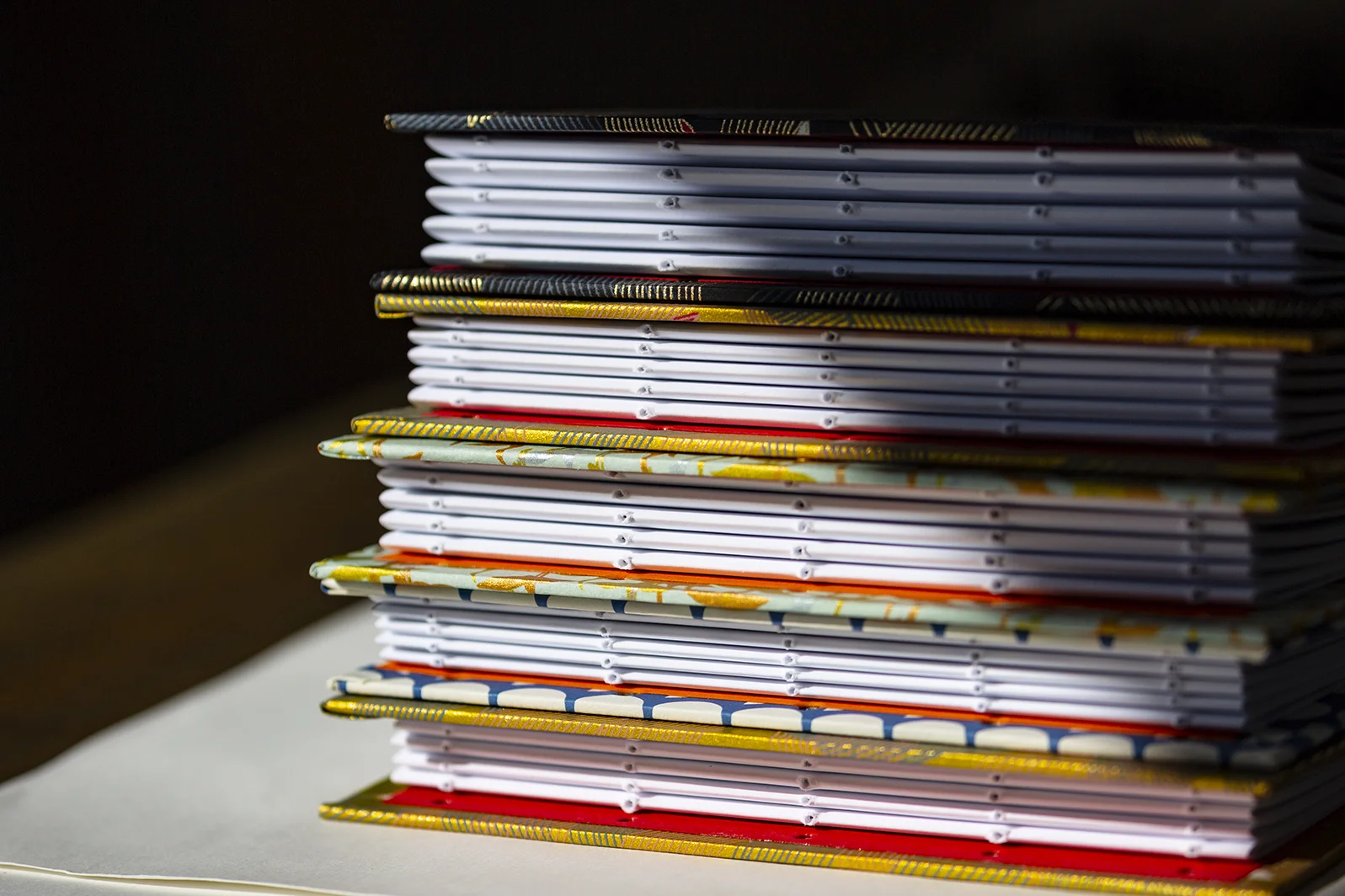

Make it

Latitude began as an approach to looking at landscapes differently. But it also became a project about making: about hand-printing images both digital and analogue, and about creating a book with my own hands. As the project progressed, as I learned more about the principles and processes of production, I began to discover a great joy in the making of books: in choosing, folding and trimming papers for the best possible image reproduction; in selecting threads and hand-stitching a spine; in finding beautiful decorative papers in which to bind the finished object. Latitude is an exploration of my own photographic art, but craft is integral to the project too. It is important that these images and this book are made objects, things produced by hand, by me. Latitude has been an enormously rewarding journey in which I feel I’ve allowed myself to take some different directions and, as a consequence, have developed both as a photographer and a maker. I hope that this project, this made object, these images, this thing, might take you on a journey just as rewarding as my own.

You can purchase limited edition fine art, giclée prints from the Latitude project here.